It’s summertime in New England. Along with the pleasures of beautiful hikes, searching for golf balls in the woods, trips to the Vineyard, and long walks with the dog, comes the danger of tick bites.

It’s summertime in New England. Along with the pleasures of beautiful hikes, searching for golf balls in the woods, trips to the Vineyard, and long walks with the dog, comes the danger of tick bites.

Worried? You should be. If you live in Massachusetts like I do, then you live in a Lyme endemic area. In 2014, for example, the Department of Health and Human Services reported 3,830 confirmed cases of Lyme Disease in Massachusetts. Worse, I believe that this number is a gross underestimate due to underreporting. Perhaps there are thousands of cases of early Lyme Disease treated in physicians’ offices which go unreported. Equally concerning is that according to the 2016 data, the incidence of Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, and Babesiosis, two other tickborne illnesses in Massachusetts, is on the rise.

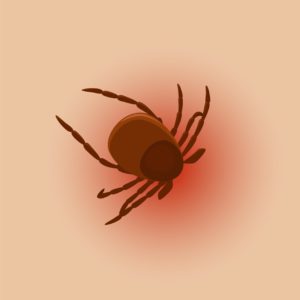

If you’re interested, here’s the biology of ticks as it relates to disease transmission. The deer tick (not the dog tick) is capable of transmitting Lyme Disease. Not just any deer tick, but a female deer tick in the larval or nymph phase of her life. A nymphal deer tick is most prevalent in the spring and summer, and is approximately the size of a poppy seed. Now, the nymphal tick needs a blood meal in order to survive and continue to develop, so she wants to attach to a host in order to feed on the blood of the host. Unfortunately, some nymphal deer ticks have a bacterium (Borellia burgdorferi) living in their stomach. While feeding on the blood of its host, the tick will regurgitate some “saliva” for lack of a better term, and transmit the Borellia burgdorferi bacterium to its host. This is the cause of Lyme Disease.

I would be remiss not to mention that what you really should know about tick bites is that you should prevent them in the first place. Be sure to stay covered when outdoors in Lyme areas. Inspect your skin, and your children’s also, after spending time outdoors. If you do find a tick, remove it quickly, so that it might not have time to transmit disease.

So you found a tick? I counsel my patients to follow these steps:

1. Don’t panic!

Remember, most ticks do not carry the Lyme organism. Furthermore, if your tick is carrying the organism, it probably takes at least 24 hours (maybe longer) of attachment to transmit Lyme or other illnesses. So don’t worry, Lyme is still unlikely.

2. Remove the tick quickly

There are a few reasons to remove the tick quickly. First, if the tick has not yet burrowed, it is easier to remove it before it does. Second, removing the tick before it has had a chance to transmit its bacteria is an effective way to prevent illness.

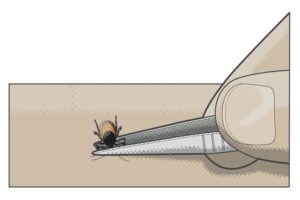

3. Remove the tick correctly

Please please. No vaseline. No baby oil. No matches, or thread, or hydrogen peroxide, or magic potions! First, clean the area with some rubbing alcohol or iodine if you have it. Then, using simple household tweezers, grasp the tick with the tweezers parallel to the skin, as close to the skin as possible. Now, gently apply traction to pull the tick up off of the skin. Do not twist, bend, rock, or otherwise contort the tick to remove it. This will increase the chance of breaking the body off of the head.

Please please. No vaseline. No baby oil. No matches, or thread, or hydrogen peroxide, or magic potions! First, clean the area with some rubbing alcohol or iodine if you have it. Then, using simple household tweezers, grasp the tick with the tweezers parallel to the skin, as close to the skin as possible. Now, gently apply traction to pull the tick up off of the skin. Do not twist, bend, rock, or otherwise contort the tick to remove it. This will increase the chance of breaking the body off of the head.

4. If you remove the body, but the head remains in your skin, don’t try too hard

I get many phone calls in the summer from panicked patients with a tick head embedded in their skin. My advice is to try gently and briefly to remove the head again with the tweezers, but that’s all. Aggressive attempts to remove the tick head, such as digging with sharp devices, peeling skin, etc. pose far more harm than good. If the head remains, it’s okay. Leave it. Your body will naturally extrude it, and this does not cause disease.

5. Save the tick in a sealed plastic bag

Tick identification can be helpful at times for clinical decision making. Your doctor may ask to see the tick.

6. Call your doctor

Depending on certain circumstances, prophylactic antibiotics may be necessary. So let your doctor know if you found a tick. A few pills might be prescribed (usually not though).

As always, I hope this helps.

Off for a hike in the woods,

Dr. Van Dam